ZIYANG WU & MARK RAMOS

Generazione Critica: Could you tell us about your artistic journey and how you decided to focus on your respective fields of artistic research, on the one hand how digital technologies impact our media, socio-cultural, and political landscape, and on the other hand reflecting on our futures through 3D programming and model development?

Mark Ramos: Conceptually, I’m interested in the Internet as both physical infrastructure with a planetary-scale geopolitical reach as well as site of complex socioeconomic and cultural interaction, an asynchronous conversation addressed not only through more established critical and academic writing, but also through the ways people interact online: memes, UI, and new media.

Lately, I have been working pretty exclusively on the web, making websites that question or are intended to be subversive towards the ways that we are conditioned to be online, interact with technology, perform a role in a network. As an artist, I’m also interested in pushing the capabilities of the browser with 3D graphics, webGL, and other frameworks as methods. I want to make work that encourages people to do what they aren’t supposed to do on the web.

Ziyang Wu: My recent practices examine how current technologies, in a cross-cultural context, affect politics, society, and the explicit and implicit relationships between things at both macro and micro levels, in the form of field surveys, data analysis, real-time simulation, augmented reality, video game, and interactive video installation. The themes of my recent projects include “Algorithmic Control and Bias,” “Digital Labor Rights,” “Community and Immunity,” “Planetary-Scale Computation,” and “Evolution of Cloud Network Societies.”

As a project-based artist, the medium of my artwork is always based on the theme of the project. For example, in “Where Did Macy Go?” I responded to the large number of ineffective online exhibitions during the pandemic (such as simply replicating a “white box” online) by aiming to leverage the most effective functionalities of the internet and social media: stickiness, sharing, and virality. Therefore, I divided the nonlinear narrative of “Where Did Macy Go?” into 11 episodes and released them on TikTok weekly, similar to a TV series, to enhance the “stickiness” of the work. Additionally, I utilized methods such as continuously inviting friends to share and purchasing advertisements within my capabilities to maximize the spread of the work as widely as possible. In “24 Panda,” I focused on the pervasive exploitation of free digital labor. I downloaded 24 free 3D panda models from Sketchfab (one of the world’s largest 3D model platform) and placed them in a fantasy forest scene. Ultimately, these artworks were sold in the form of NFTs. Leveraging smart contracts, half of the proceeds from each sale were divided by 24 and distributed back to each creator who provided the free models.

GC: Your works, while presenting some aesthetic differences, do converge on some themes of great common interest. Indeed, you both investigate the influence that a “data-driven” society exerts on users’ behavior and ways of thinking, as well as the effects that artificial intelligence and automated communication technologies have on the ways in which information is sought and consumed and on social relations. Equally important, you both turn your attention to the ongoing environmental decline, to which the current political forces seem not to be paying due attention. We would be curious to know how your artistic collaboration came about and what is your respective approach to the projects you work on together.

MR + ZW: We met as members of New Inc’s Art & Code track that’s mentored by Rhizome back in 2020. New Inc is the New Musuem of Contemporary Art’s Incubator for people working at the intersections of Art & Technology and Rhizome is an historic organization dedicated to preservation, curation, and critical writing of born-digital work. Part of our track included collaborations with engineers at Nokia Bell Labs, as a continuation of their long-running Experiments in Art Technology program. When the pandemic forced everything online, we worked together with engineers from Bell Labs remotely to make the work “Networked Ecosystem.” We were lucky our first work together debuted as part of the Rhizomes: New Art Online series at the New Museum. Since then, we’ve continued to collaborate, on a work called “future_forecast” in 2021/2022 and the work on display at Metronom now: “Event Modeling.”

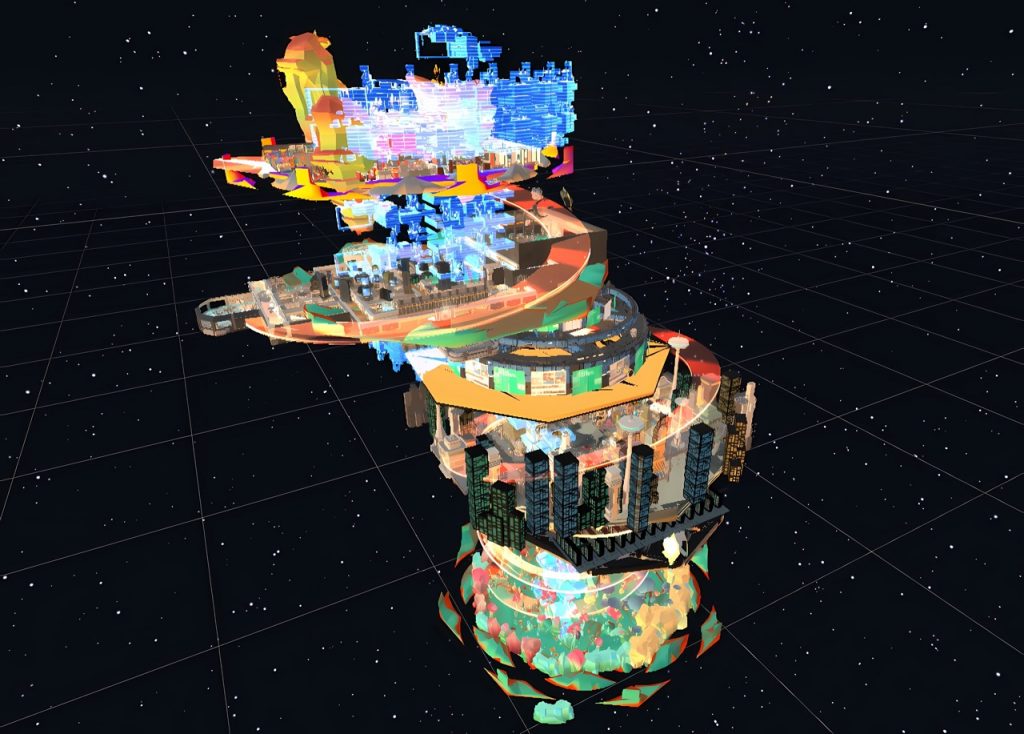

Wu Ziyang & Mark Ramos, screenshot of the “Stack” structure in “Future Forecast”, 2022. Live simulation and collective world-building online environment, 2022. Commissioned by Guangdong Times Museum, Media Lab.

MR: Since Ziyang is in China, and I’m based in Brooklyn, NY, we conduct divergent lines of research semi-independently from each other and then meet online regularly to discuss conceptual frameworks. Practice-wise, I like to say that Ziyang often has a stronger role on the front-end: the 3D modeling, the aesthetic style and composition, the visual language. I usually work more on the back-end, on the code, working with the script or game engine.

GC: “Event Modeling” crystallizes over time, in the form of digital fossils, different happenings extracted from the media landscape proposed by the algorithms of social media platforms. In essence, it describes how our reality is mediated and profoundly changed by digital technologies. Can you tell us about the genesis of the project and your respective role in its development? What is the role of each of the two parts that make up the work, “#dump” and “AI Fossil?”

MR: I worked directly on the part of the work we ended up calling “#dump.” We wanted to create a real-time simulated landscape for the AI text-to-image generation models Ziyang had been experimenting with during his residency at Alfred University. We referenced strip and mineral mines as well as landfills as places where technology’s demands on the environment were visually apparent in these lurid, neon colored pools of liquid byproduct. We wanted the work to be responsive to real-time tweets on X as a way for everyone to participate in building this environment. It’s a kind of unintentional generative collaboration triggered by social media presence. It’s a digital landscape littered with artifacts of the current gestalt, remnants of networked presence.

Ziyang Wu & Mark Ramos, Event Modeling, #dump, 2023, live simulated online environment

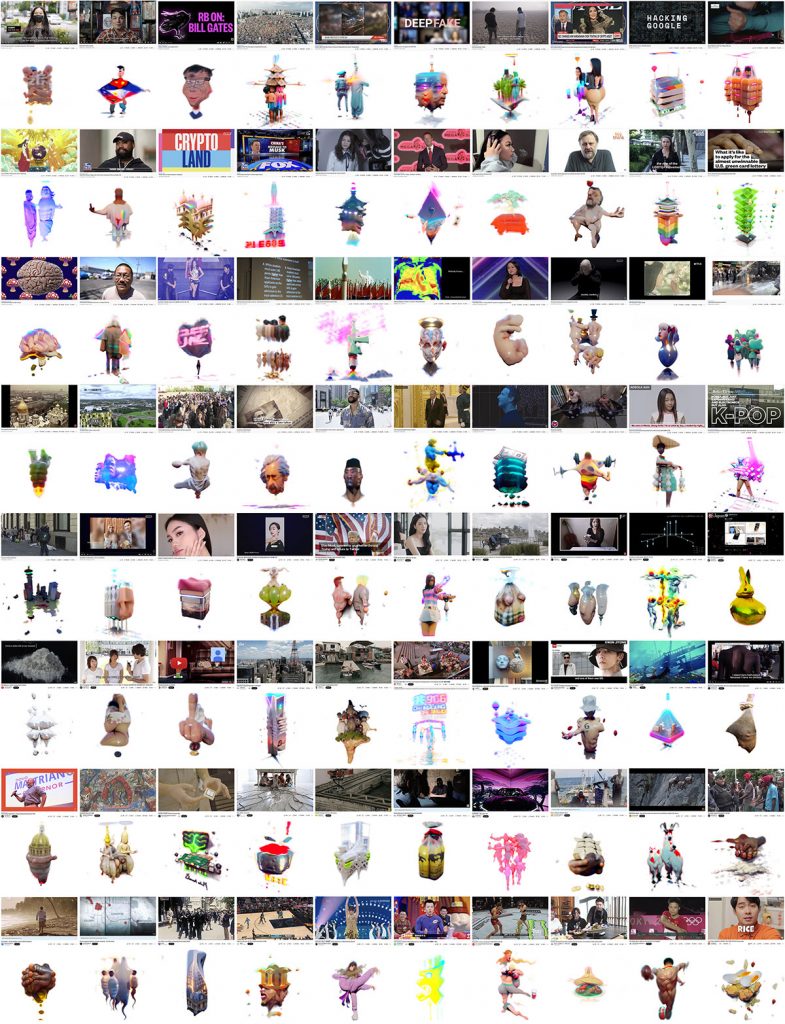

ZW: As Mark just mentioned, the “AI Fossil” part started during my residency at Alfred. During that time, a friend of mine introduced a text-to-3D AI generation tool called dreamfields3D. Since we have been working with 3D model for a long time, we were very excited about its potential. So, I collected and organized various news and social events that had occurred or were ongoing (over the period of 81 days), based on the daily push notifications from social media algorithms. I then used the dreamfields3D to generate corresponding 3D models for each material, with the headline text of each news serving as the input sentence. In the era of AI explosion (albeit perhaps in its infancy), we attempted to transform various human information into “AI fossils” by recording them as 3D models through text generation technology. In the future “abandoned factory” scene that is mixed with reality and virtual, participants can find their original text by approaching each “fossil”, and they can also dig out stories that have become grand, obscene, meaningful, exciting or moderately boring in the AI generation process.

Event Modeling – AI Fossil, video still.

© Ziyang Wu & Mark Ramos, courtesy the artists.

GC: The work extrapolates its information from different platforms. And these, in turn, rely on the algorithms that regulate the flow of content. Can you tell us about the sources of the project and, if and how, did you train the algorithm of the different digital platforms to come up with a certain type of information rather than others?

MR + ZW: This is actually an interesting question from a technical standpoint because we needed to use three different programming techniques to scrape the data for “#dump.” The processes themselves were sort of dictated by the way the specific platforms were built and rules/legalities around the Internet in general in this time. The original Twitter bot (pre-X) used an open-source API that at the time was freely available for anyone to use. Researchers, artists, developers were able to freely access this kind of data and do things like find the most recent tweets etc. When Twitter rebranded as X, they shutdown these API endpoints and anyone that wanted to access this data had to pay on a scale of $100/$1000/$4000 month which priced out most artists, including us. For about 6 months, we were able to use an open-source project called Nitter that bypassed Twitter’s API by scraping the front-end sql data. We were able to kind of replicate this technique for one of our bots since Nitter has no back-end API and scrape Tweet text from the front-end html divs. The Nitter project was pretty much killed by Twitter over the course of 3 months in the beginning of 2024. In the Summer of 2023, I was in China for an academic fellowship where I worked on a bot that scraped Weibo (Chinese version of Twitter) through a very backdoor route. Weibo maintains a legacy version of a mobile site for older android devices that is relatively unprotected on the front-end. Building off tutorials I followed from MIT, we were able to build a bot that accessed the JSON data used to build these pages. Three different bots, three different coding approaches through trial and error to accomplish the same functionality: find the latest tweet linked to a hashtag and feed it into our “#dump” simulation to trigger a 3d model dump.

Full list of AI-generated 3D models and their seeding information/source media.

© Ziyang Wu & Mark Ramos, courtesy the artists.

GC: The essay “Keywords for Today,” which you employed in the production of your work, provides an overview of the evolution of contemporary society’s history through significant keywords. In fact, it has also been called a sort of vocabulary to understand the 21st century. Can you tell us why you approached this text and what were the most representative keywords in the development of “Event Modeling?”

MR: I think part of the selection of this text was driven by the social media API’s themselves. Most of them relied on hashtags as identifiers for the posts so we needed a way to find relevant hashtags. Ziyang found and researched this specific text more than I, since I was working more on the coding part.

ZW: When we decided to realize “#dump” through live simulation, we were thinking which would be a broad enough system that could both cover most of the theme on social media, and keep the conceptual quality of the project. So the book “Keywords for Today: A 21st Century Vocabulary” came to our mind. I think all keywords are extremely important for the project. Because they are all extremely important topics in our world today, such as Truth, Violence, Trauma, Technology, Sexuality, Race, Political, Occupy, Network, Love, Gender, Feminist, Evolution, Depression, Democracy, Class, Capitalism, and more.

GC: The project began in 2023, so it has not been a very long time since its beginning, but would you be able to say whether during this period, up until now, it has been possible to identify any trends among the spawning of the 3D artifacts extracted from the news proposed by the digital platforms?

MR: Interesting question! For me, part of the visual interest has been in seeing in the simulated landscape pile up with models. I like watching them pile up on each other in precarious structures. It’s like this repository of digital artifacts of online activity. I think there is a definite shift in current subject matter that cuts across hashtags. For example, earlier in the development of the work NFT tweets were really popular across hashtags and more recently, tweets about AI and Palestine.

GC: In your work, Ziyang, the use of live simulation is a recurring aspect. Another interesting element is the introduction of worldbuilding concepts for the creation of simulated digital worlds equipped with their own ecosystem. Unlike classic fantasy worldbuilding, the worlds you create imagine future scenarios that explore various themes, including today’s environmental changes, the relationships between technology, AI and nature, and the socio-political challenges of the future. Could you elaborate on your development process by working with live simulations and the creation of fictional worlds? What are your inspirations and thoughts behind this choice? How do live simulation and worldbuilding allow you to explore these issues?

ZW: Conceptually, we are both interested in data-driven society, social-political challenges and environmental issues. For example, in “future-forecast,” we explored the evolution of cloud network societies in developing countries, with the Philippines as a representative case. One of the most important components of the project is a real-time simulation combined with a collective world-building online game. The real-time simulation part involves connecting a series of real world data related to the Philippines, such as climate and environmental changes, to the virtual space through APIs to trigger various effects and changes in objects. The collective world-building aspect involves players completing a series of tasks designed based on preliminary research. After successfully completing tasks, players can “build” and permanently alter the landscape of the project. Ultimately, it becomes a future cloud network society, created collaboratively by real-world data and various decisions made by players in the game.

Rather than presenting the work in a didactic manner, I’m interested in world-building through the construction of a complex system and implementing various types of inputs (such as real-world data or decisions based on different players’ ideologies). For instance, players can decide on what they believe to be the correct way of development: planting a tree in the Earth layer or constructing an alienated “tree-shaped” signal tower; in the user layer, hiring a human employee or an AI employee; in the city layer, choosing between deploying IoT and blockchain technologies for panoramic surveillance and network colonization to monitor and govern river channels in real time, or letting garbage flow freely in the water. Faced with the vulnerable social ecosystem, should one opt for “low-energy” biological wisdom or “high-energy” digital surveillance; choose the advantage of sensory embodiment or the risk of governance machinery? For me, these constantly iterated, unknown, and fluid “futures” based on complex systems may be closer to reality.

GC: Mark, in your artistic practice, the role played by open source platforms is very important towards making information and knowledge free, an approach to digital technologies which was very strong in the 2000s and which unfortunately is now gradually being lost with the privatization of content and access to information. But not only that, the use of software and platforms is now almost entirely controlled by subscription solutions that grant the final user the use of products and tools through a perennial rental. On the one hand, we no longer really own the tools with which to create content and information, on the other, these same contents are subsequently quantified and deemed suitable by algorithms. In this post-apocalyptic landscape, what do you think could be valid re-appropriation strategies that users can implement to slowly regain control over knowledge and access to it?

MR: I think these are big questions that benefit from a multitude of approaches and frameworks. One of the exciting promises to me about speculation about web3, is the idea of decentralization which is also part of a dialogue of returning the means of production and ownership of our online selves to the people that use them. I like to imagine a space where people on the internet aren’t just users, and networked interactions are more egalitarian collectively imagined by everyone. For me, part of this is in my studio practice of decentralizing technology from the user end, looking at labour within these systems, looking at who supports these systems, and looking far away from “the ideal user” as a way to guide a new kind of technological framework as well as in reclamation of tools and methods.

GC: What are your future projects? Is there anything else that you would like to add?

MR + ZW: We’re looking at AI propaganda generation and its role in some important recent political decisions in parts of Asia, rewriting historical narratives, and scripting memory, perception, and nostalgia. More soon!

Ziyang Wu & Mark Ramos, Event Modeling, #dump, 2023, live simulated online environment