SABRINA RATTÉ

Generazione Critica: From 2011 to the present, your work has gone through a very interesting evolution aesthetically, materially, as well as in terms of the themes addressed. In your early video works we can find influences from early computer art, as well as from video art; works like “Aurae” (2012) made me think for example of Ed Emshwiller’s “Scape-mates” from 1972, while in your more recent ones there is an interesting approach to worldbuilding, with the construction of environments hanging between past, present and future. Can you tell us about your artistic journey and its development?

Sabrina Ratté: Yeah, in the early days, it was all about experimentation with the medium of video and how to access or generate images. I wasn’t that into film at the time, and it took me a while to realize that video was a more natural fit for me.

My initial question was, “What makes video different from film and other media? What are its unique qualities?” That’s how I discovered video synthesizers, which were analog tools used by pioneering video artists. They were incredible because you could directly manipulate electricity with knobs and wires. It’s amazing and beautiful to see the results.

So, video synthesizers really took me into this world with a very different approach compared to, say, 3D animation. It’s very direct and hands-on, which definitely influenced my aesthetic, the way I see and create things. In those days, it was more of an experimental approach with the medium, trying things out and letting meaning emerge from the process itself.

Eventually, while doing this, I became interested in creating more complex environments, more than just manipulating individual images. I succeeded in creating that complexity, but it also involved the distribution of images [arranging or presenting them]. As you mentioned, I still use video synthesizers in my work, but it’s more about how they can affect the final piece in different ways. I try to keep all of these artistic languages alive in my work, constantly adding new layers.

GC: Another interesting aspect of your work is the sound element that complements your works. Your collaboration with Roger Tellier Craig is a long-standing one also. Please can you tell us about how sound integrates with your work and how did your collaboration start?

SR: So yes, we’ve been working together for a long time. I first started collaborating with Roger Tellier Craig, who’s been in a very important Montreal band for ages. He’s dabbled in many genres and now does a lot of film work. He’s also very interested in electroacoustic music. He has a lot of different skills and experience across genres. Back then, we were both really into electronic media and had a duo together. He would create the visual life for my projects, which was really cool. We toured a lot, and I also directed music videos for him. But it was always a two-way street. He would sometimes create music for my videos based on the specific ambiance and feel I was going for. It was a very interesting dialogue.

We don’t collaborate in the same way anymore, but we still work together a lot. Actually, we’re currently in a residency together exploring artificial intelligence. It’s really cool because AI completely changes the way we work together. Now, he uses AI to generate both sound and images. This connects back to your first question. We’ve evolved together over the years – for 15 years actually. We’ve both continued to explore different tools and mediums, from analog to digital and now AI, always in a kind of parallel dialogue. Our artistic worlds are very much intertwined. We basically keep building layers together. Additionally, video and its history are deeply connected to electronic music.

GC: That’s interesting.

SR: Yes, like I mentioned earlier about video synthesizers. They’re based on the same technology as music synthesizers, but instead of sound, they output colors. I could use his video synthesizer and his music synthesizer together with mine. They’re truly complementary mediums, and their history continues to be intertwined, even now with AI and digital tools. It makes sense that sound plays such a close role in my work.

GC: So it’s not like the environment and video come first, and the music comes second, or vice versa. They develop alongside each other in your work.

SR: Well, to be more specific, I would typically give Roger the final video concept and then lately, we’ve been working on things like, for example, imagining the sounds that fluorescent creatures might make.

GC: In your work there is a progressive emergence of material forms, in the guise of objects, bodies, natural and architectural elements. The transition from the abstract to the material component is very organic. Can you tell us about this aspect of your work and the role played by photogrammetry and 3D object scanning?

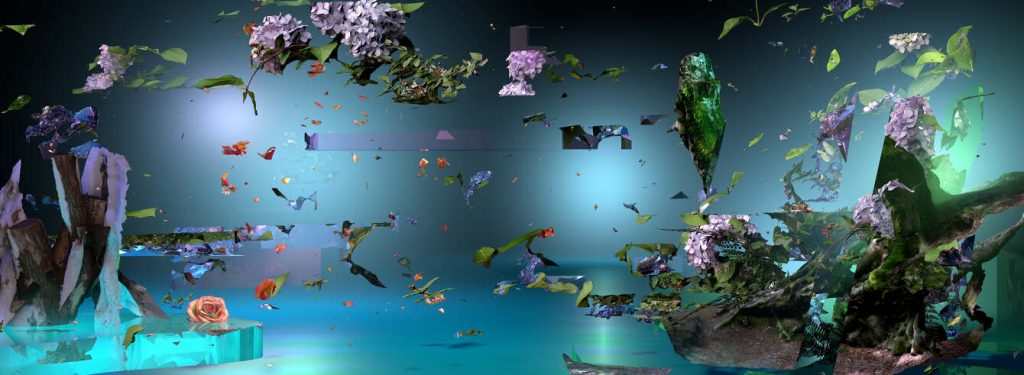

SR: “Objets-monde” was actually the first piece where I started to be interested in trash as an object. And in this context, I wanted those objects to be more architectural. Very big objects in the landscape. So the landscape would be maybe more referencing that natural world. With my project “Inflorescence” (2023), I pushed this idea of garbage and the natural world even further. As a digital artist who relies heavily on technology, I became curious about the lifecycle of technology itself. Where does all this equipment we use end up? We constantly chase the newest models, leaving older ones behind. It’s a major issue. We often ship our waste to other countries, creating a global mess. It’s difficult to recycle some of these materials, and there are significant political roadblocks to solving the problem. These objects we create serve social purposes, but they far outlast our own lifespans. They remain in the landscape for centuries. And that was the starting point for “Inflorescence,” for example. What if, I thought, all this garbage piled up, and life emerged from it?

Imagine creatures that combine organic and technological elements, half-formed from the remnants of our discarded electronics. These “cyborg creatures” would draw a residual energy from the lingering electricity within the trash. It was fascinating to create a world where humanity has vanished, but new life has sprung from our waste.

Sabrina Ratté, Inflorescences, 2023, video still.

A production of the New Now Festival, Essen, Germany. Multimedia integration: Guillaume Arseneault. Sounds: Roger Tellier Craig.

© Sabrina Ratté, courtesy the artist.

GC: That reminds me of the Chernobyl disaster. The abandoned power plant is a monument to destruction, yet nature has begun to reclaim the area. Plants and animals have adapted to the radiation, and the site itself is teeming with life. It’s a powerful contrast.

SR: Absolutely. Events like Chernobyl inspire my work. It’s a testament to life’s resilience and its ability to adapt and re-emerge. I’m currently working on a new project that delves into speculative evolution. I’m exploring what life might be like, say, 20 years from now. There’s a whole subgenre of science fiction dedicated to this concept, but it’s not very widely known. It’s a fascinating topic to explore.

GC: “Objets-monde” explores the relationship between human activity and the environment through the reproduction of an ecosystem in which human traces become emblems of what once was human existence, almost a kind of memento mori in a nostalgic landscape. Would you tell us about the genesis of the work?

SR: The French philosopher Michel Serres has been very influential. The traditional definition of an object is something tangible, something you can hold and discard. But there’s a broader concept emerging. It’s the idea that objects can also be intangible forces that permeate our lives. For example, consider nuclear energy, the internet, or satellites. These are forces we don’t necessarily hold or see, but they profoundly impact our world. They’re vast and invisible, unlike physical objects. On the other hand, I’ve been thinking a lot about garbage lately. Watching documentaries about waste, I realized it’s another kind of object. We bury it, and it accumulates in massive landfills, like the infamous garbage island in the ocean. It becomes a physical presence in our environment, even if we try to hide it. You can find tiny pieces of trash everywhere, even in parks.

I like to think of garbage as a new kind of landscape element, something that’s permanently altering our surroundings. This perspective made me consider the future. What will remain after humans disappear? Unlike the beautiful ruins of Roman or Greek civilizations, we’ll leave behind a different kind of legacy – plastic and other non-biodegradable materials scattered across the globe. I wanted to explore this idea in my artwork. The landscape you see in the video is actually created using satellite data from Google Maps. It allows me to see the world from a vast distance, where garbage and cars appear as these enormous, alien structures.

Speaking of which, there’s a specific anecdote that sparked the whole project. I was inspired by a recent experience in Quebec, Canada. It’s a very forested area, but while working there, we stumbled upon a strange sight – abandoned cars in the middle of the woods. Plants were growing over them, creating a surreal and unsettling image. It felt very apocalyptic, but also strangely nostalgic. The cars were a reminder of a bygone era. It was a beautiful and terrifying sight at the same time.

GC: That’s fascinating.

SR: There’s a kind of sublime beauty in that tension. That’s what I try to capture in my work – the feeling of being caught between something beautiful and terrifying. It creates a state of ambiguity and leaves you questioning what you’re seeing. When I saw that image of the landscape from space, it resonated with this idea. It sparked a whole new direction for my artwork. Those abandoned cars actually appear in the video itself.

Sabrina Ratté, Objets-monde, 2022, 177 x 118 cm.

A production by Le FRESNOY – Studio national des arts contemporains (Tourcoing). Interactivity: Guillaume Arseneault. Soundtrack: Roger Tellier Craig.

© Sabrina Ratté, courtesy the artist.

GC: In this work, but not only in it, an important role is played by memory, which made me think of a proximity to, for example, Anne and Patrick Poirier’s environmental installations, which highlights the fragility of anthropological time, outlining a continuum between past and future, individual memory and collective history. What can you tell us about this aspect?

SR: The concept of time is really interesting to me. I’m fascinated by the idea of collapsing past, present, and future into one experience. In my videos, for example, in “Inflorescence,” I integrate elements from the past, present, and future. I use electronic objects, even outdated ones like old VHS players or TV for example. And then in the same piece, I have these structures that symbolize future ruins, so, I’m deliberately mixing different time periods within my work. I’m exploring the possibility that in the future, we might exist as digital archives, remnants of our current physical selves.

Sabrina Ratté, Inflorescences, 2023, video still.

A production of the New Now Festival, Essen, Germany. Multimedia integration: Guillaume Arseneault. Sounds: Roger Tellier Craig.

© Sabrina Ratté, courtesy the artist.

GC: I’m curious about the recurring theme of plant life in your work. What inspires these creations? Do you base them on real-world plants or do you invent fantastical flora for these environments?

SR: It’s a little bit of both, actually. Lately, I’ve been very inspired by abstract visuals. They might not be readily identifiable, but they spark images in my head. These initial ideas act as prompts, launching points for further exploration. However, there’s also a painterly side to my work. While I can’t exactly say I “paint” in the traditional sense, digital art and video allow me to “paint” with light and pixels. As someone who appreciates aesthetics, I’m drawn to formal elements like composition and color. Colors are a particular passion of mine.

And everyday objects inspire me too. Interestingly enough, I find discarded items to have fascinating stories. Here in Montreal, I see people throwing everything away on the street. It’s like unintentional assemblage art. These discarded objects piled together become a kind of cultural commentary. So, my inspiration comes from a blend of sources – abstract prompts, real-world observations, and even intuitive connections to my readings.

GC: Your videos have a very distinctive color palette. The colors and atmospheres feel carefully curated, contributing to the overall aesthetic. The worlds you create are strangely real yet dreamlike – not quite one or the other. I like that tension. The way you blend realism with a touch of the fantastical.

Sabrina Ratté, Objets-monde, 2022, 177 x 118 cm.

A production by Le FRESNOY – Studio national des arts contemporains (Tourcoing). Interactivity: Guillaume Arseneault. Soundtrack: Roger Tellier Craig.

© Sabrina Ratté, courtesy the artist.

SR: Thank you. While I may not use traditional tools, I do approach my work with a painter’s eye for composition and color palette. It’s a great way to describe my process, especially when you see the work on a large screen. The overall composition is truly powerful.

GC: I would be very curious to know more about your process of worldbuilding, of building environments populated by different elements. What is your starting point and how does this creative process unfold between prints, interactive installations and videos? How do the different creations connect with each other, along with the notion of speculative evolution?

SR: I’m fascinated by the concept of subjectivity. Our experiences filter our perception of reality, like virtual reality creating a utopian world. Everything we encounter shapes how we see the world. In a way, we each live in our own constructed realities. Every piece of art, book, or photograph is a world unto itself. For me, creation is an act of welcoming the subjective. Speaking of which, what I love about speculative evolution is its vast room for imagination. It allows for world-building, but also evokes a powerful force beyond our control. Evolution is influenced by so many factors over such a vast timeframe. It’s something that happens entirely outside our control, yet we undeniably impact it. That’s both frightening and fascinating. Horror movies often explore this fear of uncontrollable evolution, with mutated creatures or unforeseen consequences.

Ultimately, speculative evolution speaks to our most primal experiences – our biological reality. That’s why I’m so interested in biology and authors like Lynn Margulis. And of course, a huge fan of David Cronenberg’s work – his focus on the body resonates deeply. There’s a paradox here. As we become increasingly virtual, living more and more in online worlds, perhaps this will push us back towards the physical. It might make us more aware of our bodies and our embodied experience of the world. This tension is something I explore in my own work as well.

GC: Another interesting aspect of your work is that there isn’t a negative contrast between the machine world and the human world, it’s not a situation like “machines vs humans”, but everything evolves organically I’d say.

SR: Absolutely. You captured my thoughts perfectly. It’s about moving beyond an anthropocentric view and seeing the world from a different perspective, not always through a human lens. There’s so much to explore in this concept.

Sabrina Ratté, Floralia, Wallpaper 800 cm x 293 cm.

Images and soundtrack composition: Sabrina Ratté. Sound design and mix by: Andrea-Jane Cornell.

© Sabrina Ratté, courtesy the artist.

GC: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

SR: I am currently taking part in a 7 weeks residency, Roger Tellier Craig is there too, and I am working on AI and speculative evolution. It’s very interesting because before this, I was dabbling a little bit with AI but I couldn’t really find my entry point, so this is the perfect opportunity to do it. Also, the residency is in Sherbrooke, Quebec and I can go there back and forth so this gives me time to reflect on my work. I am sharing little pieces here and there on my Instagram profile so feel free to have a look around.