NOAH LEVENSON

GC: Your research focuses on artificial intelligence and the role that AI has on everyday life, from facial recognition technologies to its use to target and monitor online consumer activities. At the same time, your work has extended to fields that are different from each other, while also complementary: computer science and digital technologies, the video game industry (Mario Kart Live), and the realm of contemporary art with Stealing Ur Feelings. Can you tell us in more detail about your field of inquiry and the various facets that make up your work? What led you to work with AI?

NL: I think my projects reflect my evolving perspective on the role of computer technology in our lives. Ten years ago, I was much more interested in pure innovation – in other words, leveraging emerging research to build fun and technologically sophisticated things that nobody had ever seen before, like Mario Kart Live. Today I’m much more pessimistic. We have a surplus of fun and convenient things but we’re becoming much less free. Now, I think that if you know how to write software, you ought to be figuring out how to make people more free.

My work with AI follows the same trajectory: I was initially attracted to deep learning because it’s mathematically fascinating, and I spent a while working as a computer vision engineer. But now my curiosity has turned morbid, and I’m mostly just watching from the sidelines as the growing AI industry creates another wave of authoritarian alliances between big corporations and big government.

GC: Stealing Ur Feelings was created with the support of the Mozilla Foundation and highlights how Big Tech companies are using increasingly refined technologies to decode users’ emotional states, what they feel disdain for or interest in, and use those indicators to create an emotional profile of people. How did the project come about? Can you share with us the development process of the work as well, from its conception to its release?

NL: When you use a social network, everything you do is a vector for data collection – all your likes, all your uploads, all your chats, all the games you play, it’s all part of the surveillance program. One day it dawned on me that the silly dog face filter was probably no exception to this rule, and that tech companies were likely using computer vision techniques to extract data from our selfies. Facial emotion detection seemed particularly useful to Big Tech, since companies could correlate our feelings with other inputs from our devices – like our geolocation, or the content we happened to be scrolling past – to infer consumer sentiment about all kinds of things.

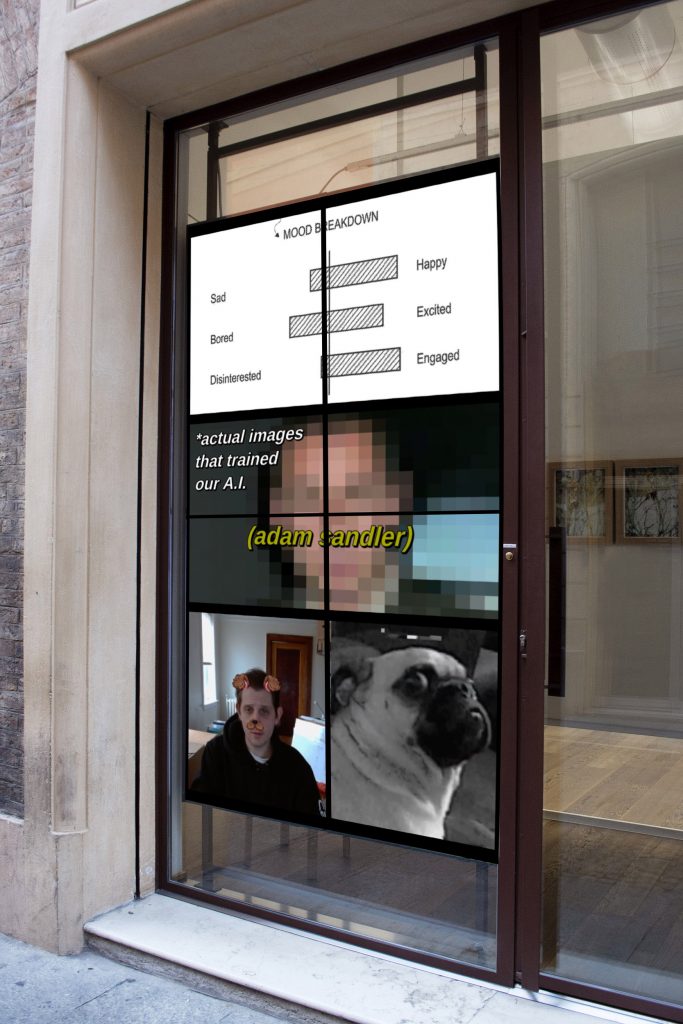

© Noah Levenson, Stealing Ur Feelings 2019, video still, courtesy the artist

At first I thought that maybe this was a bit paranoid, but after some googling, I discovered patents indicating that many companies were thinking about precisely such a strategy. Snapchat had filed a particularly dystopian patent which featured cute drawings illustrating all the places they’d like to surveil your emotions – at rock concerts, political rallies, and so on.

My plan was just to shine a light on this idea in a way that regular people could relate to. I pitched the project to Mozilla as an interactive film that would live in a web browser. I thought it’d be cool to actually perform facial emotion detection on the viewer as they watched the film – essentially “watching them back” – to illustrate the concept directly.

There were some technical complexities to figure out, mostly related to performance limitations in the browser. I’d produced a few tech demos early on which solved most of the programming problems – and we were accepted to the Tribeca Film Festival’s interactive competition on the basis of a prototype – but it was a real struggle to figure out how to tell the story.

For about 6 months, the project much more resembled a serious documentary, which I hated. I wanted it to feel funny and weird, like a meme, but I couldn’t figure out what the joke was. Eventually I discovered the central trick: we could test the viewer’s reactions to different kinds of content and classify them in increasingly uncomfortable ways. Do you prefer men or women? Do you prefer black people or white people? Don’t worry – we’ll study your reactions and figure it out for you! The result was kind of offensive, like we were trolling the audience, which I enjoyed.

The project premiered at Tribeca in the spring. I spent the summer optimizing it and touring it around a few other interactive festivals, and we released it on the internet in the early fall.

© Noah Levenson, Stealing Ur Feelings 2019, video still, courtesy the artist

GC: Here is, we have the role that companies like Meta play in creating and shaping new kinds of online habits and desires. At the same time, our digital existence is mediated by a whole series of filters, frames, and interfaces, which determine how we present ourselves to others and especially how we wish to express our personality. Our digital persona exists simultaneously on multiple levels and is in constant change, updating, shifting, in a continuous redefining loop. It is undoubtedly a precarious balance between allowing ourselves to be overwhelmed by the trends instilled by Big Tech companies, which pilot the way we express ourselves, and the need to play different personalities and seek our own creative dimension, unbound. What do you think of the extensive use of filters and interfaces that we make, at more or less conscious levels?

NL: It’s hard for me to relate. There’s nothing less appealing to me than social media. When I look around at everyone participating in it, I tend to think about smoking cigarettes. I’ve never had a Facebook account, but I smoked cigarettes for 18 years. Smoking cigarettes is a profoundly stupid thing to do. I tell myself: well, social media is like cigarettes, but for normies. Then it sort of makes sense to me.

GC: Your investigation into users’ social media use and more generally the concept of privacy has extended to other works, such as Weird Box, an interactive film in which the protagonists are photos from the public Instagram accounts of those who have decided to join in. I don’t know whether we can say that humans are by nature Peeping Toms, voyeurs, watchers, however, the fact is that especially with Instagram, and particularly with the introduction of stories, digging into other people’s feeds has become a completely mundane, almost automatic action. How did the project come about and why did it end in 2019? In your opinion, is it us watching others or is it the algorithms watching us as we look at the profiles of unknown people?

NL: Around 2016, I was trying to launch an entertainment industry startup. The startup was broadly focused on tools for injecting user-generated content into movies and TV shows. Weird Box was just me screwing around with some of our technology, demonstrating a few ideas, and trying to generate publicity for the company. When the press wrote about the project, they converged on this idea that it was a statement about online privacy. Any interpretation of Weird Box is fine with me, but my intention wasn’t to make a statement of any kind. My intention was to make people laugh and to make my startup succeed. My startup failed. I hope some people laughed.

Weird Box scrapes public Instagram data, which is not something that Instagram wants you to do, particularly not at the scale that Weird Box did it. So they made quite an effort to shut Weird Box down. Every time they developed a new trick to block us, I’d figure out a way around it. But by 2019, it no longer made sense to devote so much energy to battling Instagram, and so I shut the project down.

To answer your question about who is watching who, I think Instagram’s algorithms are selecting the class of bureaucratic loyalists who will keep the whole deranged system running in exchange for higher status and a few perks. In other words – all these plastic-faced fitness grifters, lowkey animal abusers who exploit dogs to get famous, and dudes with sick abs who cook vegetarian recipes with no shirt on – they’re essentially Instagram’s version of the nomenklatura from the former Soviet Union. They’re desperate mediocrities who will blindly glorify the platform in exchange for just a tiny bit of power. To get appointed – that is, to acquire a following – they must satisfy the algorithm. Everyone sort of intuitively understands what kind of horseshit will satisfy the algorithm. What makes a successful Instagram influencer? What made a good apparatchik in the USSR?

© Noah Levenson, Stealing Ur Feelings 2019, installation view at Metronom, Modena, Italy

GC: I often hear that paying attention to the Terms and Conditions section of online services, social media, or third-party applications’ request for access to one’s device and camera is useless “because there is nothing to hide anyway and nowadays everybody knows everything about us.” Statements like this actually reveal a profound misinformation about the use of our personal data and a lack of literacy about the treatment of our privacy by companies like Meta or Google. Reading very long technicalities, moreover written in an extremely small font, is certainly not a fun activity but perhaps it is thanks to the irony of projects like yours that we can hope to achieve a deeper awareness regarding these topics. Perhaps spaces for sharing and discussion should be created in order to achieve a more solid literacy about the use of our personal data.

NL: I’m not sure if I agree with everything you said here. In my opinion, the reason people don’t care about data privacy is the same reason that nobody votes in presidential elections: everyone knows the system is a scam. In modern America, people know that “democracy” is an illusion created by the ruling class to trick us into thinking we’re participating in a consensual government. The institutions which influence outcomes in the United States are broken beyond repair. If we suddenly had 100% voter participation, nothing would change, because the system is no longer capable of producing positive outcomes. I think people are smart enough to realize that similar rules apply to ideas like “data rights”. You can pass federal data privacy laws, form data unions, regulate the corporations, and demand “data nutrition labels” to your heart’s content, but everyone knows it will just be creating a new layer of establishment power – that is, more jobs for nonprofit executives and government employees, new corporations which capitalize on new regulatory compliance opportunities, and new policy advisory opportunities for academic experts – but the tangible benefits to the people will be very marginal. Everyone has lost hope.

GC: The role of artificial intelligence and its use to exploit user data is not only related to social media, but also to the production of visual works by AI such as Midjourney, which, as the website states, “aims to expand the imaginative powers of the human species”. Recently, however, many artists, especially the freelance illustrator community, have objected to the unconsented use of their art to train AI to create images. There are those who see no problem in that, since it is merely a way to precisely train AI without appropriating the work of others, and those who perceive such interventions as violations of intellectual property, even to the point of foreshadowing a possible replacement of the role of the artist themselves, in multiple fields. For example, the video game High On Life appears to have used Midjourney to add the finishing touches to the game experience, and co-creator Justin Roiland affirmed how this is an opportunity to make content creation more accessible. However, for whom would it be? How do you see it? Again, is it really our imaginative abilities to be amplified or is it just another way to let new services and algorithms finally dictate our imaginative thinking as well? Anche in questo caso, sono davvero le nostre capacità immaginative ad essere amplificate o è soltanto un altro modo per lasciare che nuovi servizi e algoritmi guidino finalmente anche la nostra capacità di pensare le immagini?

NL: It’s never a good idea to play the role of moral obstructionist in the face of technological disruption. You’re going to lose. Artists complaining about generative AI in 2023 are like musicians complaining about mp3s in the late ’90s. The world is moving on. It’s deeply uncomfortable, but you have to find a way to move on with it. The creative destruction of technological innovation also creates new opportunities to be found in the ashes of the old way of doing things. It’s a better strategy to start looking for them than to sit around complaining. My opinion is that generative AI is no different from any other disruptive technology – it’s just automating a task. The automobile was useful for performing certain kinds of tasks that horses are good at. Generative AI is useful for performing certain kinds of tasks that creative people are good at.

GC: I read on your website that you have recently been tackling the problem of decentralization regarding users’ search for information. Can you tell us a little bit more in detail about this area? You are also a senior engineer at Lantern, a project that aims to provide free access to the open Internet. Can you tell us more about that? How is user data handled?

NL: Around 2019, I became interested in the problem of decentralized discovery. Most of society’s current problems are the result of human networks that have become corrupted and dysfunctional. Tomorrow’s human networks will inherit certain fundamental properties of the computer networks upon which they’re built. Client-server network architectures tend to result in lord-and-serf relationships at the human layer, and peer-to-peer architectures tend to result in something more resembling democracy at the human layer. I think it’s good to pay attention to new peer-to-peer technologies which seek to redefine technological power relationships – whether it’s something like Bitcoin, or Secure Scuttlebutt, or Urbit.

Anyway, there’s a fundamental problem in engineering called “discovery,” which is the problem of locating relevant resources for a user when they’re not exactly sure what they’re looking for. Much of the value provided by online platforms comes from their discovery algorithms – e.g., Youtube’s video recommendations, Uber finding nearby cab drivers, or Amazon surfacing similar products you might want to evaluate. Discovery in peer-to-peer networks is very hard because the database is distributed and the processes which replicate the data cannot be trusted. I set out to design a lightweight peer-to-peer protocol which solves the problem of geographic resource discovery – that is, the problem of finding resources which are located within some bounded region of physical space. Peer-to-peer geographic resource discovery forms the basis for decentralized food delivery, decentralized ride hailing, decentralized online dating, and a bunch of other application types. The hope is that this technology could eventually redefine power relationships at the computer science layer, which would redefine power relationships at the human layer, and result in less exploitation of human beings.

Lantern is a startup that makes internet censorship circumvention technology. A number of governments around the world block their citizens from accessing the open internet. If you live in one of these countries – like China, Iran, or Russia – you can download Lantern, bypass your country’s restrictions, and access the outside world. As you might imagine, the open exchange of information is even more important during periods of heightened government violence, as has occurred during the Iranian protests of the last few months. Since our users are typically breaking the laws of their home country to use our software, we are quite transparent about our privacy policy. We publish all documentation resulting from legally binding requests from government or law enforcement agencies. If you have a minute, I highly recommend that you read through some of the documents we’ve published – it’s a pretty fascinating view of state power.

© Noah Levenson, Stealing Ur Feelings 2019, installation view at Metronom, Modena, Italy