JON URIARTE

Generazione Critica: Your education was focused on photography from an authorial point of view. How was the interest for a curatorial approach born during your career as an artist? One of your first experiences was curating the “Photobook Club” in Barcelona and from here you then took part in a series of initiatives and assignments which led you in 2019 to be the curator of digital programs within the institution The Photographers’ Gallery. What was the red thread that guided you in these experiences?

Jon Uriarte: I started The Photobook Club Barcelona aiming to meet people interested on photography books. I saw on Facebook (which at that time was the most active social network) that someone was trying to start something similar in the UK and decided that I could also give it a try. It worked really good for a few years and I meet good friends while organizing the meet-ups. Then, a few years later with three friends we started Widephoto, a self-sustained curatorial end education initiative. We invited artists that we admired to come to Barcelona or other areas of Spain to lead workshops, performances and talks. We didn’t thrive economically as we hardly made even, but we managed to bring international artists as Jason Fulford or Adam Jeppesen, we won the Can Felipa curatorial open call with a nice group show and we partnered with major local institutions such as the CCCB or Foto Colectania on different projects. Almost simultaneously I was invited by Foto Colectania to curate DONE, a programme looking at the image on the post-digital era. The first of the three DONE’s in 2016 included a series of talks with no public in the building, the public was only allowed to join online. It was a quite radical proposal at that time, as it was years before Zoom even existed and we were not used to online talks at all. However, we reached a quite interesting audience through that programme. Later on, I was one of the selected curators on Parallel, a European platform for artists and curators, where I had the opportunity to curate an exhibition at Le Chateu d’Eau in Toulouse (France) and to meet many international colleagues. While I was working on that, I joined The Photographers’ Gallery where I’ve been curating the digital programme since the summer of 2019. At the same time, I was invited to curate Getxophoto, one of the most prestigious photography festivals in Spain that takes place in the streets and unconventional spaces of Getxo, in the Basque Country. Given that my role at TPG is part-time, I was able to simultaneously curate Getxophoto from 2020 to 2022.

It might sound naïve but I enjoy meeting people to share interests, opinions, questions and ideas with them. Exhibitions can be a great format to do that and I really enjoy working with artists although sometimes it can be difficult to get a real knowledge exchange with the audience. Other formats, such as Screen Walks, a series of live-streamed events that we started in 2020 together with Marco de Mutiis, digital curator at Fotomuseum Winterthur, offer a straight forward interaction with the public that I particularly appreciate on that sense.

I also keep a strong curiosity towards ideas, technologies and popular practices that are new to me, and to share and discuss what I’ve learned with others. Those interest have kept me close to education and research, two fields that I also enjoy engaging with.

GC: Inside the programming of The Photographers’ Gallery, as responsible of the digital department concerning visual culture and photography, you curate the Media Wall, a permanent exhibition space born in 2012 that for its peculiar position on the outside wall of the institution streams H24 video content. From its very beginning with the exhibition “Born in 1987: The Animated GIF” in 2012, the Media Wall is defined by its constant focus on digital transformations in photography and how the digital culture is defining our approach to images. I think for example at “Camera Ludica”, the video essay by Marco De Mutis which explore the use of photography inside video game presented on the wall in 2018; or furthermore the contribution by Tamiko Thiel with “Lend me your Face!” in 2021 in which the artist explores the ability of learning machine to replace the person’s face with someone else’s. Do you think that with the experience of the Media Wall it was possible to create a communication, both artistic and educative, with the public? And what kind of motivation lead you through the programming of it?

JU: When I joined The Photographers’ Gallery in 2019 the Media Wall was the main display of the digital programme. It had been showing digital artworks since 2012 when Katrina Sluis was appointed the first curator of the programme. It was located on the ground floor having a privileged location as the first display that visitors would encounter as they came in. It was visible from the street across the windows, making it also accessible for passersby even when the gallery was closed. It’s location by the Gallery cafe, over the stairs down to the Bookshop and the Prints & Sales gallery on the lower floor made it also special, as it wasn’t the usual white cube scenario. The ground floor of the gallery can be busy, with visitors walking up and down the stairs or chatting on the cafe. Even if the surrounding context were challenging in terms of offering live interaction and getting the attention of the public, it’s scale (2.7 x 3m) and its location right in the entrance of the Gallery made it very visible and accessible. The challenges that the Media Wall faced within the institution could make a nice metaphor to the ones that digital culture faces when being shared on social media platforms. It’s challenging to reach your audience when navigating spaces where the attention economy is ruling.

On the other hand, I believe that many of the works that were exhibited on the Wall shacked the traditions of photography intensely, successfully raising many eyebrows crossing the doors of the Gallery every day. The works that you mentioned and other commissions by well-known artists as Heather Dewey-Hargborg, James Bridle, Anna Ridler or Joana Moll challenged many photographic notions and invited to approach visual digital phenomenon that are usually regarded as superficial, as for instance the LOLCats, with a rigorous and playful approach. Other relevant questions as the digital image production techniques and process’, the impact of social media and its politics, the emergence of machine vision and its development were addressed during the 10 years of the Wall.

For the LOL of Cats: Felines, Photography and the Web at the Media Wall

Photo: Andy Stagg

When the building closed during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, the digital programme team worked with the commissioned artists to create online extensions of their works that were published on unthinking.photography, our online platform. Soon after that, the Media Wall was decommissioned as exhibition space becoming (yet another) marketing display. Since then, the digital programme has expanded beyond the screen curating installations within the building – Apian by Aladin Borioli and A·Kin by Aarati Akkapeddi –, on the streets around it on the Soho Photography Quarter – Open Space is an AR mentorship and artist commission programme taking over the new public art space on the streets around the Gallery – and online on Unthinking Photography.

GC: As curator of the digital programme in charge of the Media Wall at The Photographers’ Gallery, you could dig inside the research on photography and its digitalization. If before the interest was dedicated on the wide possibility that digital platform or systems could give, right now it got very urgent and necessary to also talk about the impact that such production and proliferation of images has on the environment. The Photographers’ Gallery, in partnership with Centre for Study of the Networked Image, has started a series of publications and activities willing in research on the ecological effects of the circulation of images called “The image at the End of the World”. What is the core of this programming and how do you think that this kind of research could change our relationship with digital contents?

JU: The Photographers’ Gallery digital programme is an experimental research project. We aim to include a wide range of audience engaging with digital cultures including Gen Z teenagers using facial filters, computer scientist who develop the software to make them possible and academics trying to unpack those tools and practices. We regularly collaborate with universities on events, symposiums and long-term research projects and just opened the third round of a collaborative PhD scholarship with the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (CSNI). The two previous researchers were Nicolas Malevé who worked on the “Algorithms of Vision. Human and machine learning in computational visual culture” thesis, and Marloes de Valk and her ongoing research on the material and social impact of the networked image on the climate crisis.

Both research projects have become part of the core interests of the digital programme. Nicolas Malevé greatly contributed to unthinking.photography, he showed a work at the Media Wall, conducted experiments with the Gallery staff, and was very influential on the development of Data/Set/Match, a yearlong programme looking into visual datasets. Similarly, Marloes de Valk’s research has been key for us to learn the environmental impact of the technologies we use, and to develop several programmes such as the series of commissions and activities we did to coincide with the COP26 meeting in Glasgow or the most recent Small File Photo Festival.

GC: Concerning this attention to the impact that a digital image can have on the environment, you have organized in January 2023 the “Small File Photo Festival”: the festival is encouraging and celebrating the small size photography which means to show artworks that have a specific low weight in kilobytes. The festival started from an open call for contribution: how was as curator to go through such specific content? And do you think it will be possible a digital Renaissance in which small images would replace the obsession for large-files?

JU: The Small File Photo Festival was suggested by Marloes de Valk who, as previously I mentioned, is working on her PhD with a collaborative scholarship between the Gallery and the CSNI. She was familiar with the Small File Media Festival which was founded by the scholar Laura Marks in Canada four years ago, and suggested that we could follow their example. Our festival included an open call for small file photos that received more than 400 submissions from many different countries. During the festival we hosted a workshop with Restart Project where participants took a smartphone apart and learned about its components; a photo walk by DigiCam.Love – a network of retro digital camera enthusiasts; a series of talks and presentations; an award ceremony, and an online exhibition with the shortlisted and wining submissions.

All the events and activities were well attended by a mixed community of people. Some of them interested on retro digital technologies and their aesthetics, and some others with an environmental concern. Responding to your question, we don’t aim to replace high-res images with smaller size files but to start thinking on the material impact that those technologies have and collectively explore other possibilities that might be as interesting in terms of their aesthetic and poetic possibilities. It is obvious by now that we’ve reached a tipping point of the extractive capitalist system in which besides the emissions, the nonrenewal resources will become scarce. The promise of the endless increase and improvement will need to be confronted soon and we need to find alternatives, also in the field of photography and digital arts.

GC: “The Image at the End of the World, Small File Photo Festival” together with the program of activities made in 2021 “COP26: Sustainable Photography in an Unsustainable Wold?” are examples of the need to bring into the specialist and no specialist audience such themes. What is the goal for you inside such cultural activities and what is the next step you would like to make into this area of research and artistic production?

JU: The COP26 and the SFPF both originate in connection to Marloes de Valk’s PhD research. They are our attempts to create an accessible and engaging public programme drawing from the academic research that she is working on. Our goal is to translate the research into another language that can be reached and participated by our audiences. The next step on that is to publish several articles on Unthinking Photography that will accompany the ones that we’ve published so far.

At the same time, our aim is that the research projects that we are part of not only have an impact on the curatorial programme. They also have motivated changes on the infrastructures that we use, as for instance migrating the hosting of Unthinking Photography to a green hosting or taking part on the Gallery environmental task force.

GC: Going through your career it is clear that you have a very deep and profound bond with images, it is even possible to see a kind of romanticism behind the way in which you relate with the visual content. I think for example at the experience of “You must not Call it Photography If This Expression Hurts you”, a collective initiative that aim to provoke the traditional photographic discourse. Photography for you seems to be an identity to talk to and to relate to as if it would have its emotions and feelings. What are your wishes for the grow of photography in the future where it seems to be less and less attention and cure towards images and more an obsession and abuse of them?

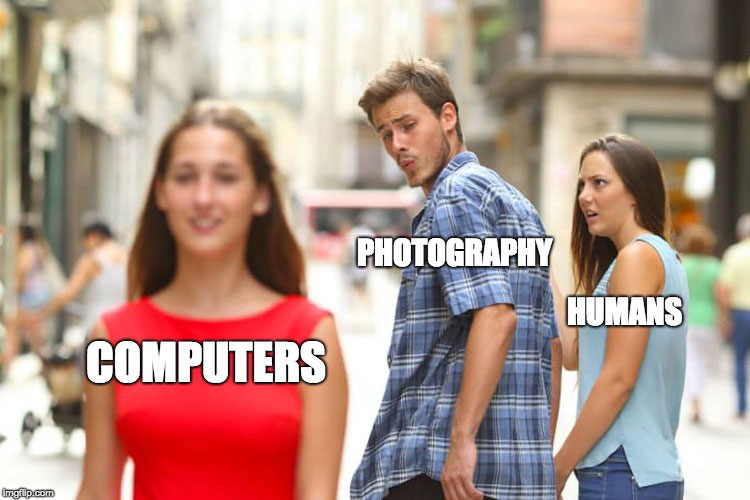

JU: “You Must Not Call It Photography If This Expression Hurts You” is a collective that Katrina Sluis, Marco de Mutiis and me started to challenge the traditional notions of photography. We played with the romanticized idea of photography as an identity because that’s one of its usual tropes. As an example, the death of photography has been announced so many times by those who wish to maintain its status quo, that it could be considered a zombie by now 🙂 .

I don’t have any interest for photography to grow, it’s interesting and complex enough as it is and it keeps getting more and more complex very quickly. I do wish that the organizations, collectives and individuals that champion, practice and preserve it realize and get up to date with the dramatical changes that the medium is going through. Much of the thinking about photography is looking into dated practices that only exist within photography institutions themselves, while the corporate and everyday photographic cultures have shifted somewhere else. They still seem to be trying to reclaim its place along other artistic practices, focused on canonizing its own traditional specificities as part of the western history of art, instead of paying attention, questioning or engaging with how it is evolving.

Source: http://youmustnotcallit.photography/assets/img/selection/meme_photography_computers_humans.jpg

I don’t think that photography is getting less attention. It has lost significance as a representational tool but networked images are very relevant economical assets, political propaganda instruments or playful everyday communication elements to mention a few of its other roles. It’s being economically squeezed, politically weaponized and has become one of the most relevant elements of the networked social fabric.

If we only think of photography as carefully hand-crafted prints hung on a frame with a passe-partout, then we might think that a selfie with that framed photograph circulating on a social media platform is abusing it –even if using the term abuse towards a photograph doesn’t feel right as it makes an unfortunate anthropomorphizing comparison. But if, for instance, we think of that selfie as a method to publicly present oneself in connection to a particular artist/artwork/topic/aesthetic/exhibition space other more relevant questions might arise. We could also question the algorithmic politics that take part on the process of circulating and making that image visible; or on the accessibility and reach that user documentation photographs shared on social media offer to physical exhibitions; or about the technical process’ that take place when snapping a smart phone computational image; or on how that image can end up becoming part of a large dataset used to train machine vision algorithms and what’s the impact that it could have. But if instead we keep on thinking about photography enclosed within its traditional framework, then we will most likely only be able to keep on whining about its death.