CASSIE MCQUATER

For the new screening of “Chun-Li” by the artist Cassie McQuater inside the program FILTRO, third edition of the DIGITAL VIDEO WALL curated by Gemma Fantacci, Generazione Critica has interviewed the artist.

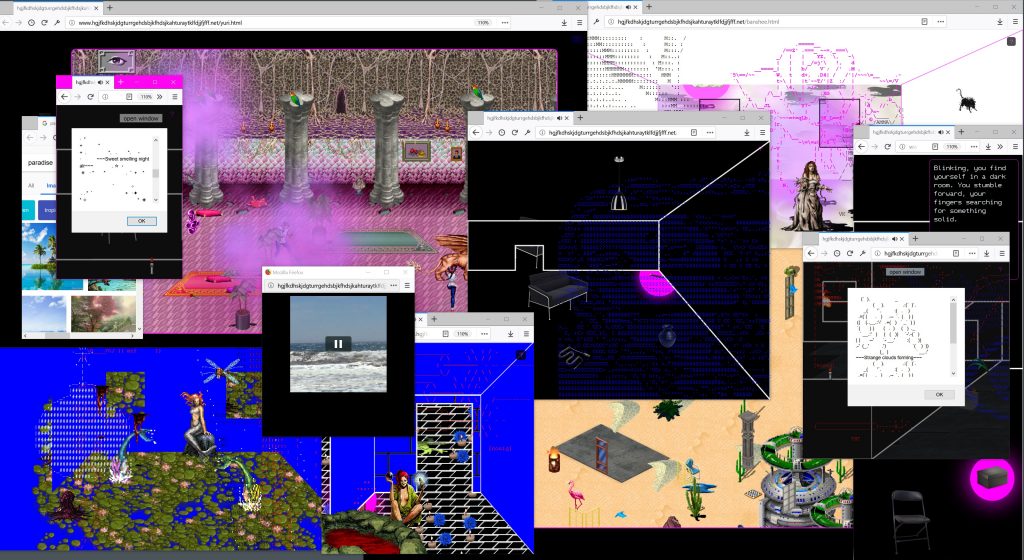

Generazione Critica: In a recent article for The Architectural Review, Rob Gallagher defined one of your projects, Black Room (2017), as an example of autobiographical bricolage. In a broader sense, your artistic practice can be described as so, as your work incorporates a wide variety of media, such as GIFs, video-games’ references, sprites, retro aesthetics and so on. Can you tell us about your upbringing and delve into the several media that inform your art?

Cassie McQuater: I was introduced to video games through my grandmother, who played often. She suffered from difficulty sleeping and insomnia, and when I would spend the night at her house, I would stay up late into the morning and watch her play Zelda. I was not allowed to have my own console at home, so going to grandma’s was my only access to video games. This created a more emotional attachment, a sense of place and time, in the way I viewed and participated in gaming. I went to art school and received a BFA in painting, but still all of my paintings were informed by characters, quests, and actions manifested through collage. In my practice now, I still use collage as a starting point for narrative creation – I’m drawn to the associations we as humans make to objects, events, items and how we come to attach meaning to them, and use them as a means to create emotional landscapes in our lives.

GC: A recurring element within your work is the subversion of the misogynistic and chauvinist aesthetics of arcade fighting games. The female avatars are freed from the extremely sexualized conventions and then reintroduced into a tableaux vivant that breaks any connection with the original game. How do you identify the game systems you want to hijack and how do you envision the avatars in a new setting?

CM: I often start with a character I encountered in the games I was able to play as a child, because I feel connected to that character in a deeper way. I also like to use characters that are easily recognizable, with others that are not. So, in a tableaux, perhaps the extremely recognizable character of Chun-Li is interacting with a minor woman enemy from a more obscure video game. This shows that the sexism imbued in these characters goes very deep – it does not start and end with main characters but filters all the way down to minor enemies and hostages – a deeper cultural implication.

It’s also important to me to identify where these characters came from, which consoles, what year, what publisher. This is to show that the sexism written into the characters doesn’t occur in a vacuum, and has been a way for me to begin to identify corporations that were (and still are) complicit in this representation.

GC: Your artistic practice is defined by a strong visual aesthetic, which in a sense also poses as a bridge between very different artistic periods. On one hand, it recalls the grotesques of the Italian domus; on the other, the satirical photomontages of Dada. Another work of yours, Angela’s Flood (2020-2021), refers to the central panel of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1480-1490) while replacing its subjects with sprites from fighting arcade games placed in an HTML page. What’s the relationship between digital images, game spaces and works of art from the past?

CM: Well, for me, this really goes back to my obsession with and enjoyment of the idea of collage. I break things apart and find the spaces where they can reconnect, and see what stories are born from that process. I am very influenced by the works of surrealist painters, like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, and science fiction writers, like Octavia Butler and Ursula Le Guin. So, I draw from those inspirations already – it’s not a big leap from literature to painting to coding to video games for me. I like working in a space where associations from all of these things live and rely on each other to tell a story. It reminds me of how real life works: it’s messy, does not fit in a single box, and emotions and feelings are not exactly linear throughout our lives.

GC: Images have lost their indexicality, i.e. their physical tie to their referents, and became composite images, that is, ‘an assemblage of discrete elements from different moments and sites of recording into a unified visual field’ (Williams, 2017). In an era where digital images are basically strings of data and pieces of information, and ultimately a source of money, do you think that they will face another turning point if the Metaverse (as imagined by Facebook) will really happen?

CM: I think there is a big differentiation to make between discussing digital images as data and discussing that data as a source of money or potential capital. I think just because an image is digital, materially composed of magnetic flux that’s then rendered to our screens, instead of something visible such as paint on a canvas, that does not make it inherently more or less likely to be monetized. The monetization of the image happens outside of the image itself. Whether a piece of art is good or bad, something subjective anyways, doesn’t affect how much money it will be sold for. Capitalism defines that for us, and tells us the worth of the image based on the absurd idea of monetary transactions. We already sell images for money, a practice or mode that has existed for at least hundreds of years. What the Metaverse might change is the mode of the transaction, nothing more. And if that mode of transaction involves burning enormous amounts of gas or fuel, such as many cryptocurrencies do already, it will continue to devastate the environment of our already devastated planet.

GC: A while ago, I attended a panel on the live streaming platform Twitch and some speakers talked about how the female body is subjected to the male gaze and how girls who play live are verbally harassed. One of them said that, in her opinion, female streamers who consciously decide to adopt a provocative and sexy attire are actually exploiting the weaknesses of the male audience and subverting the male gaze from within to their advantage, as they are capitalising on views. Do you consider this approach subversive? Isn’t there a risk of still perpetrating that toxic mindset?

CM: Yes, I love this. Intent is really important. If someone is acting with intent, and feels more powerful because of it, that’s a great subversion. In a way this reminds me of the work I do with the women characters and sprites – I don’t change their animations, their clothes, or their actions, but rather I remove them from their previous context/ gaze and allow them to live outside of it.

And critically, the risk of perpetuating a toxic mindset doesn’t start with the person who that mindset is injuring. It’s the fault of the people who are verbally harassing women that this mindset is perpetuated, and all of the blame and accountability to change that mindset falls on them. Women are just trying to survive in a world not built for them to do so, and whatever makes them feel more powerful, in charge and able to cope and hopefully thrive in it, as long as they aren’t doing harm to anyone else, is positive.

GC: Our media landscape is characterized by filters and visual norms developed by powerful tech companies that influence how we present ourselves under the guise of freedom of expression and creativity. Even in our own group of friends and family, we find ourselves overwhelmed by a whole set of expectations that we, as females, should obey. It’s 2022 and still the toxic and oppressive imagery associated with the fair sex and the damsel in distress is still alive and well. Do you think there are even more disruptive actions that we haven’t yet explored to try to crack the status quo?

CM: I think the most important thing is to find the courage to live your life exactly how you want to, to be authentic to yourself. I think that capitalism does everything it can to stifle that. And I think that there needs to be a revolution in both our societies and our minds to overthrow it. It may sound defeatist or a little absurd, but that is the only way I see forward.

I mentioned my love for Ursula Le Guin earlier, one of her perhaps most well known quotes as of late applies here: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

GC: I’d like to talk about another aspect of your practice, that is, the free distribution of your work over the web as a way to give back to online communities. Can you go into this aspect in more depth?

CM: I like to offer as much of my work as I can for free, on the internet, because a lot of my work is made with resources that I found for free on the internet. I like an open source mindset, the idea of giving back to those who helped you get to where you are, and the possibility of others being able to build on what you’ve given. It’s something I try to emulate in my real life and something I think is vital to real life community building, so it seems appropriate that it should also apply to my work.

GC: Lastly, you participated in the recent exhibition Pieces of Me by Transfer Gallery, a ‘response to the aggregate hype of the emerging global NFT market and the dystopia surrounding its boom’, as the website recites. This market is another example of speculative finance between white male collectors and artists. The topic is very tricky to discuss but, in your opinion, for how long will this bubble last and what would need to change for NFTs to become a true revolutionary tool in order to change the art system?

The big word here is “revolutionary.” But there is nothing revolutionary about a new way of selling something, a new currency that at its best might make a very small number of people a lot richer very quickly, and at its worst will contribute in no uncertain terms to the destruction of our planet’s ecosystem. Another important detail is that NFT’s are simply defining a *monetary transaction* in exchange for a service or good. That’s not what revolution looks like – that’s just more capitalism. Revolution looks like income equality, public services, unionizing, mutual aid, and care for each other. NFT’s will disrupt some parts of our day to day, but will never move the needle in a meaningful way towards class equality. So, call it what you will, I say, but don’t call it a revolution.

Cassie McQuater is an American artist living and working in Los Angeles, whose field of investigation sits at the intersection of new media and video games. She received her BFA in painting from the University of Michigan School of Art & Design in 2009, is a self-taught programming artist, and began working with interactive media and video games in 2013. Recently, her work has been featured at the Smithsonian American Art Arcade, for New Museum’s First Look: New Art Online, at numerous DIY arcades and international independent game festivals. She has won several awards, including the Independent Games Festival Nuovo Award 2019, the Rhizome micro-grant for net.art and the Lumen Prize for Art and Technology 2019. She has also participated in the exhibitions Radical Gaming at HeK (Basel, 2021), the Milan Machinima Festival (2020), SAAM ARCADE at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, 2019), 24/7: A Wake-Up Call for Our Non-Stop World at Somerset House (London, 2019), as well as other international events.

© Copyrights Metronom

24/03/2022